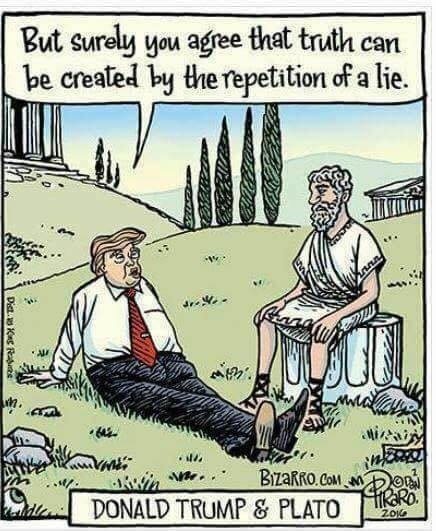

A romantic image of the great philosopher, by Dan Piraro.

I learned philosophy of language in the dogmatic antiquity of a couple of years ago. Many of my colleagues and senior philosophers seem still to cling to these dogmas, like “a sentence is made true by its disquotation.” In the now-times, though, it seems especially important to show where we went wrong in developing our theories of truth and meaning, leading us to serious mistakes like “the cat is on the mat” being true when the cat is on the mat, and false when the cat is elsewhere.

Philosophers have long held the idea that, if the utterance of a sentence is fixed by its context, then it has to be fixed by the context of utterance and then the work is done. If I say: “I am working on my dissertation,” the meaning of that sentence is fixed by the fact that I’m the one saying it and the time I said it. But that can’t be right. After all, if I say “I am working on my dissertation” and my adviser discovers I am actually spending all of my time writing parody blog posts, I haven’t lied. I just meant had been working on my dissertation for a few hours after our last meeting a month ago… the truth of the sentence goes wherever I tell it to go!

The great philosophical minds of our generation have spoken. They can change a sentence to its negation, irrespective of the fact that it does not cohere with the other sentences uttered at the same time, without a problem.

Consider a thought experiment. A speaker is asked a question about whether he trusts United States intelligence officers (call one of them “Dan Coates”) or the President of Russia (call him “President Putin”); the former says “Russia launched cyber-attacks against the United States” and the latter denies this. The speaker responds:

My people came to me, Dan Coates came to me and some others, they said they think it’s Russia. I have President Putin; he just said it’s not Russia. I will say this: I don’t see any reason why it would be. But I really do want to see the server. But I have — I have confidence in both parties.

On the old views, we would think that the speaker means he trusts both parties and that there is no strong reason to be compelled one way or the other. But this is a mistake, because it turns out that at a later time, the speaker will say that the word “would” should have been “wouldn’t,” and therefore this clarifies the issue, that “So I have great confidence in my intelligence people, but I will tell you that President Putin was extremely strong and powerful in his denial today.” This is a radical revision, so that he doesn’t see any reason why the Russian’s wouldn’t conduct cyber-attacks against the United States.

I can hear these philosophers of language moaning, “but the substance doesn’t really change; both utterances hold that he trusts both parties and is agnostic about whether or not Russia launched cyber-attacks.” This is a mistake. Because, you see, by changing the word “would” to “wouldn’t,” he changes the sentiment completely.

“I don’t see any reason why [Russia] would be [responsible],” denies that there is any evidence to blame Russia, while leaving open the possibility; by contrast, “I don’t see any reason why [Russia] wouldn’t be [responsible]” denies that there is any evidence to exonerate Russia, while leaving open the possibility. Both of these are strong, very different statements with two different effects: he isn’t sure that Russia didn’t do it and he isn’t sure that Russia did it.

He is totally clear that he… doesn’t have a strong belief about the issue.

Further, many philosophers of language make the mistake of thinking that if you say two things in conjunction, then you’ve said each of the two conjuncts. But this is wrong.

If I say, “I had some coffee. Later, I had a cheeseburger.” that definitely doesn’t mean that I had some coffee.

Consider another thought experiment. The speaker says,

“I would have done [Brexit negotiations] much differently [than Theresa May]. I actually told Theresa May how to do it but she didn’t agree, she didn’t listen to me. She wanted to go a different route. I would actually say that she probably went the opposite way. And that is fine, she should negotiate the best way she knows how. But it is too bad what is going on.”

This seems as though it is a criticism of Theresa May and her Brexit negotiations, but that is only true if it happens by itself. If the speaker also says a bunch of other things (like that one of her political opponents would be well-suited for her job) then the speaker didn’t criticize Theresa May.

You see, philosophy had conjunction totally wrong!

We used to think that if a speaker criticizes Theresa May and praises Boris Johnson, then the speaker has criticized Theresa May. But this is not so! After all, if the sky is grey and it is humid, that doesn’t mean the sky is grey; that’s just not how conjunction works, and we know that now.

These philosophical revolutions are hugely important, and we should be greatly appreciative of the contemporary geniuses that have produced these ideas.

I look forward to continued explorations of these issues this fall, when I take up residence as the Kellyanne Conway Chair for Alternative Facts at Trump University’s Bowling Green campus.

For those who couldn’t tell, this was a parody article brought to you by a delirious madman on a break from writing about supervenience and two-dimensional semantics.

James DiGiovanna

July 18, 2018

I once had a student try to argue that (A ^ B) did not entail A. I think he would have done well in the current administration.

LikeLike

Joe

July 24, 2018

Politicians are not known for being precise that is true. It is actually not new though.

LikeLike